"The Whiskey Rebellion: A Test of Federal Authority and States' Rights"

In the early years of the newly formed United States, one event stood out as a crucial test of federal authority and the balance of power between the federal government and individual states: the Whiskey Rebellion. This uprising, which took place in the western frontier regions of Pennsylvania during the 1790s, revealed the challenges of taxation, the limits of federal power, and the question of states' rights.

Casey Adams

9/21/20234 min read

Background: The Whiskey Tax and Its Rationale

Following the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the United States faced a staggering national debt.

To stabilize the economy and assert federal authority, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton proposed a series of financial policies, including the controversial whiskey tax, part of his broader plan to centralize economic control and strengthen the federal government.

The Excise Whiskey Tax, signed into law by President George Washington in 1791, was the first tax imposed on a domestically produced product by the federal government. Hamilton argued that the tax would:

Generate much-needed revenue to help pay off war debts.

Establish the government’s ability to levy and collect taxes.

Encourage economic discipline and loyalty to the federal government.

However, this tax disproportionately affected Western frontier communities, particularly in Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Virginia, where whiskey production was not just a business but an essential part of local trade and currency.

Western Grievances: Economic Hardship and Perceived Injustice

For many Western farmers, the whiskey tax was more than just a financial burden—it was an existential threat.

Frontier communities operated largely on a barter economy, where whiskey served as both a medium of exchange and a commodity that could be more easily transported than raw grain.

The tax, therefore, felt like a direct attack on their way of life.

Key grievances among Westerners included:

Disproportionate Economic Impact – Small distillers in the West bore a heavier burden than large Eastern distillers, who could pay the tax in bulk and at lower rates.

Lack of Representation – Many Westerners viewed the tax as another example of "taxation without representation," echoing the very grievances that had fueled the American Revolution.

Government Overreach – The enforcement of the tax required distillers to register with the federal government and pay taxes upfront, which many considered an invasion of their economic freedoms.

Regional Inequality – The federal government, based in Eastern cities like Philadelphia and New York, was seen as being out of touch with the struggles of frontier life, where cash was scarce and barter was essential.

The tax fueled resentment and resistance, with many distillers refusing to pay or actively obstructing tax collection efforts.

Resistance Turns to Rebellion (1791–1794)

Opposition to the tax began as localized defiance but escalated into outright rebellion by 1794. Western farmers harassed, intimidated, and even tarred and feathered tax collectors.

Some refused to pay altogether, forming armed resistance groups.

Tensions boiled over in July 1794, when a group of rebels attacked the home of federal tax collector John Neville, burning his house to the ground after a violent confrontation.

This event marked the climax of the rebellion and sent a clear message to Washington that federal authority was being openly defied.

Despite efforts at negotiation and de-escalation, the rebellion showed no signs of subsiding. President Washington, recognizing the threat to national stability, took decisive action.

The Federal Response: Washington Asserts Authority

For the young federal government, the Whiskey Rebellion posed a critical test of its power to enforce laws.

If the rebellion went unchecked, it could set a dangerous precedent that laws could be ignored through violence and defiance.

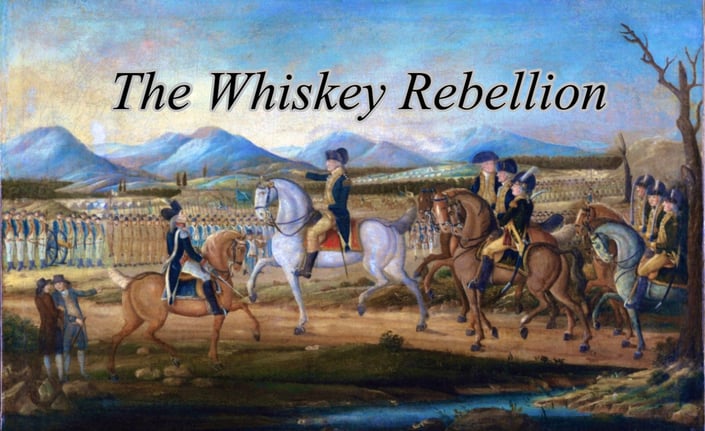

In September 1794, Washington issued a proclamation warning that continued resistance would not be tolerated. When this failed to quell the unrest, he invoked the Militia Act of 1792, authorizing military intervention.

Key aspects of the federal response included:

Mobilizing 13,000 troops from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia—the largest military force assembled since the Revolution.

Washington personally led the troops, becoming the only sitting U.S. president to do so.

Demonstrating federal resolve by marching toward Western Pennsylvania to suppress the rebellion.

The overwhelming show of force had the intended effect—most rebels disbanded without conflict.

A few small skirmishes occurred, but the insurrection collapsed without a major battle.

The federal government arrested several leaders, though only two were convicted of treason, and both were later pardoned by Washington.

Aftermath: Implications for the New Nation

The successful suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion had far-reaching consequences for the United States, shaping debates on federal power, states’ rights, and taxation.

1. Strengthening Federal Authority

The rebellion affirmed that the federal government had both the will and the capacity to enforce its laws.

Unlike the weak central authority under the Articles of Confederation, the new U.S. Constitution provided a framework for direct action against insurrection.

2. Precedent for Presidential Power

Washington’s decisive leadership set a precedent for future presidents using federal troops to enforce laws, a power that would later be exercised during crises like the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement.

3. Rising Tensions Over States' Rights

While Federalists praised the government's actions, Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican allies criticized the use of military force, arguing that it trampled on states' rights and civil liberties.

This deepened political divisions between Federalists and Republicans, shaping party conflicts in the coming years.

4. Economic and Taxation Debates

The rebellion raised critical questions about taxation, representation, and economic fairness.

Many Westerners continued to feel neglected by the federal government, fueling anti-Federalist sentiment that contributed to Jefferson’s election in 1800.

Conclusion: A Defining Moment in American History

The Whiskey Rebellion was more than a tax dispute—it was a defining moment in the early republic.

It tested the strength of the Constitution, the resolve of the federal government, and the delicate balance between liberty and order.

While Washington’s actions successfully quelled the rebellion, the underlying tensions between government authority and local resistance remained unresolved, foreshadowing future conflicts over federal power, taxation, and civil disobedience.

Today, the Whiskey Rebellion is remembered as one of the earliest and most important tests of American liberties, shaping the nation’s trajectory in the centuries to come.